Stories

-

With the school year over and nice weather upon us, I’ve had some free time to get out and explore the landscape beyond Williston. I’ve been out on the prairie twice to discover the array of early wildflowers in the grasslands. This is the time of year when I feel like I could actually enjoy…

-

My trip to the Redwoods had a profound effect on me. I can’t really explain what it was or why. I’ve been to many amazing and beautiful places never come back as humbled and rejuvenated as I had on this last trip. But everything about it just put me at ease and at awe. It…

-

When I think about the way I travel and the way others travel, there are two extremes at the ends of a spectrum: on one side, we fit in everything we can see during our limited time at a destination; on the other side, we stick to a small area and get to know it…

-

It has been quite some time since I last made a post here, so I’d say I’m a bit overdue for an update. For the past two and a half years, I have been living in northwestern North Dakota. Saying this is an adjustment is an understatement. North Dakota is considerably flatter than any place…

-

For many years, I have spent my Fourth of July basking in the part of America that I enjoy the most: its wild and natural beauty. It started in 2011 when I explored the Hobo Cedar Grove for the first time. Then again in 2013 when I hiked Grandmother Mountain. In 2015, I spent the…

-

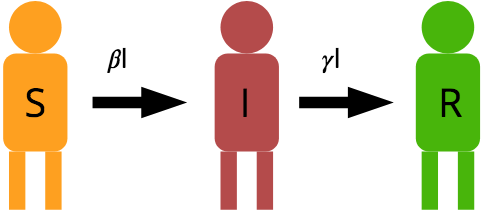

Immediately after I published my last post, I wasn’t content with the manner in which I conveyed the SIR model. Simply posting graphs from scenarios that I ran isn’t exciting. It’s passive, and it doesn’t actively demonstrate for the reader how social distancing does work to reduce infection rates. I wanted something interactive. Something that…

-

The COVID-19 virus is sweeping the world causing an equally contagious pandemic of fear and confusion. Depending on where you live, you may be ordered to stay home, going out only when necessary, or there may be no restrictions on your life, leaving it up to you to decide how to go about your day…

-

I don’t get out hiking or geocaching often these days. With geocaching, it makes sense. I’ve found nearly all of the geocaches in a close distance to home and town, forcing me to travel farther distances just to make a find. But when it comes to hiking, I have less of an excuse. I don’t…

-

In case you weren’t aware, Geocaching is one of my hobbies turned obsession that fills my life with joy. Geocaching is a game in which people hide containers and post the coordinates on the web for others to enter into a GPS and go out and find. The game began in May of 2000. On…

-

When life prevents you from going out and adventuring, you make your own adventures at home. My latest adventure is making sourdough. Now, I could go out and obtain or buy a starter from a local bakery, but what’s the fun of that? It’s so easy to start my own from scratch, and now I…

-

It’s occurred to me that I haven’t been good at writing posts recently. My last update was from May, and that was subsequently my last big hiking trip. Since then, I have been incredibly busy, and that means I haven’t had as much time for fun. I did get out a few times this summer…

-

Saturday, January 14, 2017 It’s not often that I get out to hike these days. But we’ve had a fantastic winter so far, and after a week of insanely cold temperatures and clear weather, I just had to get out and take advantage before the warm weather and rains took over. I’ve always wanted to…

-

We’ve gotten a lot of snow this winter. And then it got cold. Like, really cold. Night time lows below zero, and daytime highs hovering around 20. Â So the only thing to do with this kind of weather is go swimming. Last year, we took Clara to a developed hot spring near McCall and she…

-

When I started this site, I never expected to make daily posts. Weekly? Maybe. Monthly? Less desireable. I’m kind of ashamed that it’s been three months with no updates, but there hasn’t been much of excitement to talk about. There haven’t been any big adventures this fall. I’m just plugging away at the Ph.D. thing,…

-

In May we bought a new tent to accommodate our growing family on camping trips. I guess the two-person backpacking tent just won’t do it anymore for thee people and two large dogs. So after we bought it, we took it out for its maiden test at a nearby campground. This summer was dubbed the…

-

The Hobo Cedar Grove is a nice easy 1-mile hike through a grove of giant old-growth trees. It is the perfect hike for toddlers to explore nature, which is why we brought Clara up there on Sunday. She enjoyed the large trees, but wasn’t into walking the trail much. Eventually Erin had to carry her…

-

I finally got some time to get up to Freezeout to hike Grandmother Mountain. The flowers are out and it’s quite pretty, though it’s not the best year for flowers that I’ve seen. It could be that I got up there a little late. Everything seems to be coming out a little earlier this year…

-

It’s been over a month since my last update. There haven’t been any major adventures due to time and financial constraints. As I aim to write and finish my dissertation, the time for such outings decreases and thus this summer will be nicknamed “the summer of no fun.” Fun isn’t completely off the table, but…

-

When I moved to the Palouse, I didn’t realize just how photogenic the landscape was. Then I saw ads for the Palouse in Popular Photography. It turns out, people will pay good money to come and photograph the region, and here I am living there not taking advantage of my home turf. I’ve only been…

-

Last week, Clara and I had a day to ourselves, so we had a little adventure on a nearby trail. The white pine loop is a 3-mile hike from the White Pine campground off of Idaho Rt. 6. A one-mile (one-way) out and back spur takes us to the site of a WWII bomber crash site…